Jul 12 2018

A staple of my mis-en-place in the kitchen has always been Irma S. Rombauer’s The Joy of Cooking.

I grew up with the unique luxury of homecooked meals - both my parents were excellent cooks, whether pulling together a weeknight meal from whatever was in the pantry, or creating a complete Thanksgiving feast. My first practical cooking skills I learned from my father - he taught me to grill, to carve a turkey, to cook a bolognese. But above all he taught me the true joy of cooking - putting your heart and soul into a meal for other people to enjoy.

Our kitchen was always stacked with cookbooks. I fatefully extracted The Joy of Cooking from my parents’ cramped bookshelf and it became my first culinary textbook.

Its corners are now fraying at the edges, its pages tell stories through the smudges and stains of hundreds of meals and experiments past. It is dated in the best possible way - with crafted instructions, quaint sketches, and commentaries on cuisine - hearkening to a simpler time of homecooking, untainted by the visual demands of an Instagrammed world.

Its recipes are simple and quick to reproduce, its language casual and approachable - in stark contrast to the much more formal and complex recipes common in other cookbooks of its day.

But at the heart of The Joy of Cooking lies tragedy.

It was first published in 1931, during the depths of the Great Depression. Rombauer’s husband had just committed suicide, leaving her with two children and dwindling savings.

The Joy of Cooking was not just a cookbook - it was a treatise on self-reliance and transcendence through creation, of finding peace and meaning through food.

Where Joy of Cooking brought me into the light, Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential was my introduction to the equally-captivating dark side of the craft.

Kitchen Confidential was a no-holds-barred look into the real restaurant industry. It was an insider’s guide to how restaurants actually ran - that orders for “well-done” meat would get the worst cuts, that fish on a Monday would often be specimens from the previous week’s deliveries.

And it was a study of the people behind the stove. Bourdain’s kitchens were pirate ships, staffed with misfits and bandits, wildly intense, often cruel, slightly masochistic, but relentlessly obsessive about good cooking.

Kitchen Confidential made cooking cool. It was after reading Kitchen Confidential in high school that I decided I wanted to go to culinary school. I applied to attend Le Cordon Bleu at the same time as applying to “typical” American universities. I ended up abandoning the cooking dream, substituting my knives for a keyboard and studying computer science instead of culinary arts. But I never let go of my cooking passion, and finally this summer found my chance to check Le Cordon Bleu off my bucket list.

The day I landed in Paris to start culinary school, I found out Anthony Bourdain had committed suicide in France.

It is easy to romanticize cooking.

Cooking is the power, if just for a moment, to make people happy.

It is a science, rewarding an understanding of ingredient chemistry, melting qualities, and boiling points - and an art, blending color and form, texture and composition to convey something that is greater than the sum of its parts. A good meal requires patience, planning, occasionally quick thinking in disaster mitigation, and of course, great company.

Preparing, enjoying, and understanding food - and its partner, wine - is an intellectual pursuit of dissecting and carefully planning a creation, and a visceral, hedonistic appreciation for the creation itself.

Cooking lets you travel the world, from the curries of India to the paellas of Spain, all in your own kitchen, and share your travels with others.

Cooking lets you wander through time, from the traditional French recipes passed down through generations, to the cutting edge of molecular gastronomy and sous vide. I’ve met Vatel, Escoffier, and Childs through the pages of their books and their recipes.

But I don’t think any of this is why chefs cook. Chefs cook to fill a void - and not just in the stomach.

Cooking is one of our last remaining connections to the real.

We live increasingly detached lives in an increasingly abstract world, unrecognizable from our chimpanzee past for which our bodies and minds are still adapted. We buy, we don’t make. We communicate through glass.

But three times a day we still have to shove food into a hole in our face.

Even this we have abstracted away. We’ve created Pop Tarts. Soylent. The Chicken Nugget.

Cooking is one of the few acts we have left that is real, that is raw. It is one of our last points of connection - with the earth, with each other. It is one of the last things we do from scratch.

Holding meat over fire set us apart from our primate cousins. Cooking reminds us of this first act of human agency - that we have power to manipulate a cold, indifferent world, to make it just a little bit better.

Cooking is also fundamentally impermanent. Where other art forms are designed to last, meals are made to be consumed. Implicit in cooking is an acceptance of our own transience - that we can enjoy something in the moment and then allow it to cease to exist.

Rombauer and Bourdain shared a passion for cuisine. But they also shared a darkness. Their passion is not without struggle, not without pain.

In the face of great tragedy, of personal strife, or just of first-world ennui, cooking lets us return to our base human instinct: the drive to make our survival just a little bit more pleasant. What else is there.

Jul 6 2018

“Pretending is failing. The truth is in the flavor.” - Chef Vaca

The best way to test a chef’s mettle, as common wisdom goes here in France, is by having them prepare an omelette.

The classic French omelette is hardly recognizable next to the fluffy, cakey, slightly-browned, once-folded, stuffed-to-the-brim versions we get at diners and restaurants in the US.

The French omellete is delicate: a paper-thin layer of egg, rolled into a neat oblong, coddling a center of creamy, runny, half-cooked scrambled eggs. The French call this creamy egg texture “baveuse”, from the French word for to “drool” or “slobber.” The surface is perfectly smooth and light-gold. And in traditional French cooking, it is rarely stuffed - the eggs stand on their own, perhaps with a few fresh herbs and some salt and white pepper.

Achieving this perfect color and texture requires serious talent and experience - hence using an omelette as a litmus test for ability in a kitchen.

Eggs must be carefully cracked and scrambled - a good chef never wastes, and so pulls every last drop of egg out of each shell and the bowl. Whites and yolks must be whisked until all trace of white disappears, but no longer. The eggs are salted, then poured into a pan over high heat, and continuously mixed in a two-handed motion - the left-hand swirling the pan and controlling heat, the right whisking the egg mixture in circles with the back of a fork. Some chefs can achieve this using just the motion of the pan itself.

The eggs are swirled and cooked just until they set on the bottom, then rolled from one edge to the other - hammering the handle of the pan with a closed fist to lift the omelette up the lip of the pan to form the ideal shape. The omelette is flipped directly from pan to plate as the outside is set but the center remains “baveuse.”

We had multiple practical sessions here at Le Cordon Bleu where we practiced making the classic French omelette. The challenge was immediately obvious.

Eggs are extremely sensitive. Slightly too much heat, and the eggs will start to brown. An uneven swirl and the eggs will wrinkle. Cooking too slowly, and not paying attention to the pan, and you’ll end up with a thin crunchy crust around the edge. Imperfect whisking and you’ll have flecks of white in your final product. We make dozens of omelettes, and can’t achieve that perfect texture. The chef shakes his pan, seemingly at random, and a perfect omelette comes out in 20 seconds.

One student, struggling with the technique, asks the chef for tips to get better. The chef says “go to the store, buy two chickens, and practice.”

The humble egg is one of the most common ingredients in just about every cuisine around the globe, and holds a very special place right next to butter in the world of French cooking.

We’re all familiar with the egg’s constituent parts: the shell, the white, the yolk. But the properties of these parts of the egg - and the interplay between them - make it a remarkably flexible and dynamic ingredient.

Cooking an egg - as cooking all things - ultimately comes down to performing chemistry.

The egg contains various types of proteins, which, when exposed to heat, will unravel and “denature,” causing them to transform in texture and “set.” Proteins in the egg white will start to thicken at 61°C and set at around 65°C, whereas the yolk will begin to thicken at 65°C and fully set around 70°C.

Because of this difference, we’re able to create a broad range of different cooking styles for eggs, with very precise techniques to create the “perfect” version (at least from a classical French perspective) of each style of egg:

Hardboiled Eggs

Perfectly hard-boiled eggs are boiled 10-12 minutes, depending on size. The egg should always be at room temperature when added to the water - a cold egg added to boiling water is more likely to crack.

When time is up, the egg should be dropped in a bath of icewater, to immediately stop the cooking. Overcooked hard-boiled eggs will develop a slightly greenish tint around the yolk and an off-putting, sulfurous smell - the result of sulfur in the white reacting with iron in the yolk.

Hard-boiled eggs are most easily shelled under running water - the water enters between the shell and the white, releasing the shell.

Poached Eggs

The key to a perfect poached egg is a perfect setup.

Crucially, the egg should be fresh, less than 7 days old - as an egg ages the white tends to separate more from the yolk. The pot should be deep, and very lightly simmering - hot enough to cook the egg, but not a violent boil that will threaten to tear it apart. And the water should include a healthy amount of vinegar - Le Cordon Bleu recommends 1 part vinegar for every 5 parts water.

Create a vortex in the pot by swirling the water in a circle with a spoon, and drop the egg directly in the center - the swirling water will help wrap the white around the yolk, rather than spreading it out.

The egg should be poached two-and-a-half to three minutes - until the whites are set but the yolks are still runny. It is then similarly plunged in icewater, to stop the cooking.

And finally, an attentive chef will always ébarber their poached egg - trimming off loose strands of white to end up with a perfect, smooth result.

Eggs en cocotte

Oeufs en cocotte are eggs baked in a ramekin, with a runny yolk in the exact center of a soft white.

Preheat the oven to 150°C (300°F). Butter the inside of a ramekin, and season the base with salt and pepper. Place the ramekin in a pot of simmering water, such that the water comes part of the way up the sides, but not over the top. Add the egg, and heat in the water while keeping the yolk in the center, until the whites slightly start to set and will hold the yolk in place. Transfer to the oven for 4-6 mins, until the whites are set and the yolk is still runny.

Oeufs en cocotte make for a simple breakfast, and a wonderful base for variation. Add some heated crème fraiche and chopped herbs. Serve with toasted bread for dipping.

Sunny-side up eggs

The key to perfectly sunny-side up eggs: a ring mold.

Place a metal, circular ring mold in the center of a non-stick pan. Season the pan at the bottom of the mold with salt and pepper, so that flecks of seasoning don’t ruin the perfect surface of your egg.

Crack the egg in the center of the ring mold, and cook slowly on low heat - there shouldn’t be any bubbles in the white.

And if you prefer, finish by placing the pan briefly under a broiler to create an oeuf mirroir - a slightly shiny finish on the top of the yolk.

Scrambled eggs - French-style

French-style scrambled eggs are also nothing like their American counterparts.

Where the scrambled eggs you get in the US will have large, fluffy curds, French scrambled eggs will have tiny grains of curd - leading to a creamy, almost polenta-like texture.

Traditionally, French scrambled eggs are done in a baine-marie - a bowl placed over a pan of simmering water - to keep the heat perfectly low and the cooking slow. They can also be done in a stockpot - never a frying pan.

The bottom of the pot or bowl should be lined with butter. Whisk the eggs, and add to the pot once the butter is melted. Stir constantly with a whisk over slow heat, bringing any egg curds that coagulate on the bottom of the pot up to create a perfectly even texture. Finish with more butter, because of course.

The result should be a very fine-grained, creamy scramble - slightly flowing. Use a ring mold to plate, to achieve a perfect circle.

The “Perfect” 63-Degree Egg

The “Perfect” 63-Degree Egg is a more modern invention of the molecular gastronomy era. Cooked in its shell for one hour in a water bath, which is precisely held at 63°C using a sous vide machine, the egg comes out as a perfectly soft-poached, uniform mass - thanks to 63° being right at the temperature where the whites will set but the yolks will remain just on the edge of thickening.

Eggs are also crucial ingredients.

A combination of egg yolks whisked with a bit of cream is called a “liason.” This can be added to finish light stock-based sauces, creating a rich, velvety texture and mouthfeel. The key to a thick, creamy velouté is a liason finish.

Brush egg yolk over a pastry crust or bread before baking - an “egg wash” - and end up with a beautiful shiny coating.

Combine egg yolks with a bit of vinegar and mustard, and whisk in a neutral oil, and you have mayonnaise.

Whisk egg yolks with a bit of water over low heat, and you have a “sabayon.” The sabayon forms the basis for numerous classic French sauces, pastries, and desserts. The basic sabayon calls for about a tablespoon of water per yolk, whisked together over a bain-marie until it is thick, foamy, and runs in “ribbons” from a whisk.

Whisk in melted butter and some lemon juice to your sabayon, and you have a hollandaise. Include a reduction of wine, vinegar, shallots, peppercorns, tarragon, and chervil, and you have a béarnaise. Whisk with sugar and add vanilla and cream, and you have the base for a crème brulée.

Beat egg whites to create the base for a meringue, or soufflé.

Eggs thicken sauces. They bind ingredients together in stuffings and cakes. They leaven breads. So much of our culinary diversity would not be possible without the hidden, complex chemistry of the egg.

Often the simplest objects belie the deepest complexities; true subtelty, and broad possibility, can only reside in the mundane.

Food, like all things, can be taken to flashy, elaborate, indulgent extremes. Real, durable, enviable cooking skill though is being able to take a simple ingredient, deeply understand its properties, hone the right techniques, and ultimately coax out perfection with the swirl of a pan.

Jul 3 2018

So much of what I have picked up at Le Cordon Bleu is wildly impractical for home cooking.

Rarely will I have to behead a chicken, or gut a rabbit, in the comfort of my own home. I doubt I will ever brunoise a half-kilogram of carrots. I certainly hope to never turn a potato again.

But there are plenty of lessons that will absolutely help as I return to the life of a civilian cook.

Focus on ingredients & techniques, not recipes.

The “trick” to spectacular-tasting food is rarely in finding a magic recipe - it’s all in the ingredients, and the techniques you use in working with them.

A great home-cooked meal begins at the market. Fresh, high-quality ingredients stand on their own - they make your job easy as a chef.

Then it’s all about technique. Recipes rarely focus on technique - they list the steps you need to cook the dish, but there’s so much space for perfection in how each step is performed.

Nearly every dish we cooked at Le Cordon Bleu was remarkably simple - only a handful of common ingredients, and usually the only spices being salt and pepper. Yet from the exact same process and ingredients, the dishes the chefs make here are markedly better than what we create in our practicals. They are masters of technique.

A few examples of where technique makes all the difference:

- Sweating vegetables. The bases of most French recipes begin with “sweating” vegetables - heating them in oil or butter to soften and release flavor. Correctly-sweat vegetables make such a different in the final depth of flavor of a dish, and there are so many subtle aspects to getting it right: the right balance of fat to vegetable, the right size pan, the right order of adding ingredients, the right heat and time to let the ingredients release their flavor without browning or burning.

- Mixing ingredients. We’ll mix a liquid into a roux to thicken it, or mix liquids into flour to make a batter. You’d think “mixed” means “mixed” - just combine the two. But the key to a perfectly uniform, smooth mixture is to mix a little at first - to incorporate the two mixtures - then more and more at a time. This lets the ingredients blend slowly and evenly, minimizing lumps.

- Reducing sauces. We’ve become masters of reduction here - taking a large volume of a lightly-flavored liquid and boiling it down to create a small volume of a highly-concentrated sauce. They key is to reduce gently, using progressively-smaller pots as the volume of liquid decreases. Ingredients can scorch on the sides of a pot, leaving behind a slightly bitter burnt flavor. Too much surface area can cause a sauce to reduce too quickly, damaging the texture or flavor. A careful reduction is the key to a mindblowing sauce, and a mindblowing sauce separates the casual cook from the pro.

When it comes to ingredients, seasonality really matters.

Quality of ingredients will make or break a dish.

We don’t always have a fresh farmer’s market available to us though as we grocery shop. So how do you find quality ingredients at your local grocery store?

Stick to fruits and vegetables that are in-season. In US supermarkets - at least in California - we’re spoiled by having essentially the full range of common produce available year-round. This is a miracle of modern logistics and the global shipping industry, but a red-herring for good cooking. That winter tomato usually has been harvested while completely green and solid, and chemically ripened as it reaches its final destination.

Selecting produce that is in-season helps ensure that it has had time to develop and ripen naturally. This means richer, more developed flavors, easier-to-work-with flesh, and often also a lower price. Buying local and in-season isn’t a hippy-dippy luxury - it’s truly a win-win for any home cook.

Season, season, season.

Here to “season” a dish almost always means adding salt.

We’re constantly tasting and seasoning - meat before, during, and after it cooks; vegetables before, during, and after they are sautéed; sauces before, during, and after they are made.

A dish should never taste “salty.” But a perfectly-cooked dish, without any added salt, can end up entirely bland.

We keep ramekins of large-grained salt - similar to Kosher salt - on our workstations at all times, generously pinching it in throughout the cooking process. The salt is a natural disinfectant, and so can generally be left out in the ramekin indefinitely. It’s a must-have in any kitchen.

Breaking down meat, rather than buying fillets.

Before coming here, I didn’t know the first thing about gutting and filleting a fish.

In US supermarkets, meat is sold shrink-wrapped. It’s possible but rare to find many different varieties of whole fish. Certainly not rabbits. I can’t even imagine Safeway selling a chicken with its head still attached - even your “whole” Thanksgiving turkey will have its giblets conveniently in a little plastic bag.

At Le Cordon Bleu, breaking down meat and fish has been a large part of the instruction and technique. For fish and poultry, we’d always start with a whole animal. For meat, we’d often start with an untrimmed, un-deboned slab - even bacon for lardons would start out as a whole pork belly.

Breaking down your own meat is certainly not a no-brainer. It takes comfort and practice. It takes time. But the benefits are clear.

It’s cheaper - you’re not paying a premium for a butcher to do this for you. And you can use the whole animal for the rest of the dish. Fish carcasses would always form the basis for a fish stock, which would be used to cook the fish, and then would turn into a sauce. Meat trimmings would be browned to create sucs, to form the basis for a pan sauce. Chicken carcasses would become stock.

Breaking down meat gives you options. It gives you raw material and inspiration for additional dimensions to your dish. And it brings you closer to your ingredients. I probably won’t break down meat myself every time I cook, but it will absolutely become a part of my cooking repertoire.

Clean as you go. But actually.

“Clean as you go” is the mantra in the practical kitchens here. And I have no doubt I’ll bring this back with me - cleaning after every step when I cook.

Making a mess in the kitchen is a “boil-the-frog” problem. The mess starts slowly - a couple scraps on the counter, a dirty pan left in the sink - and slowly builds over the course of the recipe. Scraps become piles, a single pot becomes a tower, some splatters of sauce on the stove become a burnt-on crust.

Here, with a square meter of workspace, you can’t afford a mess to build up. The lack of clutter on a worktop removes that little nugget of stress in the back of your head - that nagging dread of “I’ll have to clean up all of this at the end.” Cleaning constantly actually makes the cooking process more enjoyable.

There are a few tricks I’ve learned to make it easier to “clean as you go”:

- Use a small bowl as a “counter-top trash-can.” Peel your vegetables over it, dump trimmings into it. And throw it out as it starts to fill up (or better yet, toss your scraps and peels into the compost!). This saves you trips to the garbage can, and gives you no excuse for leaving vegetable peels and onion skin on your cutting board.

- Heavy-duty “J Cloth”-style paper towels. Much thicker than your typical paper-towel, but more disposable than a kitchen rag, these are a godsend in the kitchen. Use them to wipe down counters, clean them in boiling water or even the dishwasher, and throw them out guilt-free. The chefs keep one slightly damp on their workstation at all times, to wipe down any splatter as soon as it happens.

- Wash pots and pans as soon as they’re finished. We cheat here in our practicals a bit - there’s a professional dishwasher who cleans our pots and pans as we cook. But the principle we follow carries through to home cooking - as soon as we’re done with a pot or a pan it goes straight to the dishwasher, rather than hanging out on our stove or countertop. This way they’re available to use again if needed, they don’t clutter our workspace, and there’s not a single massive effort at the end to clean every pan. At home, I’ll put pots and pans in the sink as soon as they’re done, and use any free moment during the recipe to clean whatever is in the sink as quickly as possible.

- Store multi-use tools like spoons, whisks, spatulas, and tongs in water. It’s tempting to take out your wooden spoon, give a pot a stir, and then leave the spoon on the counter. But you end up with drippings on the counter, and crusts of whatever you stirred last stuck to the spoon. I leave a small pot or measuring cup with water near the stove, with all my stirring and tasting tools dipped in it - to keep them clean in-between uses, and avoid a grungy build-up on my worktop.

- Use cupcake wrappers or small foil tins to hold cut & measured ingredients before you’re ready to use them. If you’re cutting vegetables, or measuring out spices, or prepping herbs, store them in small disposable cups to stay organized without dirtying more bowls. This way you can prepare your complete “mise-en-place” before you actually begin cooking, making the actual cooking process a breeze.

- In dire situations, plastic wrap your cutting board. If you’re breaking down something especially messy - raw meat, or scaling a fish - cover your cutting board with plastic wrap first. This lets you just bundle up the mess and throw it all out, before moving on to your next step.

Embrace the power of the scraper.

The humble plastic bowl scraper. Initially designed to get every last drop of batter out of a bowl, the scraper is easily my second-most-valuable tool (after the chef’s knife, of course).

I use it to keep ingredients in a neat pile on the cutting board - rather than scraping with the knife blade, which both damages the knife and also likely my hand. I use it to collect ingredients off a cutting board and transfer them - much neater than trying to scoop with my fingers. I use it to clean the countertop - brushing every last crumb or piece of vegetable off the edge and into my trash bowl.

It takes a little work to get into the habit of reaching for the bowl scraper, but once you get used to it you’ll never go back. Any time you take out a knife, take out a scraper.

Use the right knife for the job.

I’ve always thought that a “real” chef only needs one knife - their 8-10” chef’s knife.

I could not have been more wrong.

A key to professional-level cooking is precise cuts, and precise cuts require precise equipment.

The chef’s knife is still the anchor in my toolkit, but I’ve come to appreciate the value of each of the different primary kitchen knives.

I use my paring knife like an extension of my fingers. It’s perfect for precisely cutting small vegetables like garlic or shallots. But more often, I won’t be holding it by the handle - I’ll hold directly on the blade, and use it for peeling things like a tomato by grabbing the skin between the blade and my thumb.

I can’t imagine filleting a fish without a filleting knife - the thin and flexible blade countours precisely to the bones of the fish, making it easy to slice way flesh with minimal wastage.

And the cleaver makes it easy to process cuts of meat - even full carcasses like chicken - that I never would have attempted to tackle before.

Hone knives.

The honing steel. It comes with every complete knife set - a long, thin, cylindrical piece of metal, with a guarded handle. We can all envision chefs using this tool - deftly sliding a knife blade across it with that distinctive metallic shing.

I’ve known the purpose behind the steel - re-aligning the microscopic teeth along the very edge of a knife’s blade, to help it cut more precisely. I’ve been taught how to use it in the past - make a 15-20° angle between the blade a knife and steel, and swipe it from heel to tip, 3-4 times per side. But I’ve never really felt compelled to hone my knives in my home kitchen.

Now I can’t imagine starting to cook before honing my knives.

When you cook a couple times a week, maybe cutting a vegetable or two and never really focusing on the precision of the cut, it’s hard to really notice as a sharp knife slowly becomes less-than-sharp. Usually the dire condition of your blade will only become obvious once it starts crushing tomatoes instead of slicing through them.

But cooking multiple times a day, processing baskets of vegetables each time, an even slightly un-honed blade became painfully obvious - often literally so. A dull blade will slip on precise cuts - the easiest way to nick yourself. And it will slow your whole cooking process down, requiring more pressure and slower movements to make the same cuts.

Sharp, precise knives absolutely make a difference in the final result. More thinly, precisely-cut vegetables release flavor more readily and evenly, and lose less moisture onto your cutting board. Vegetables cut with a sharp blade will tend to oxidize less, leading to better coloring and less risk of off-flavors in your final result. And working with a sharp knife will be safer and faster.

Getting comfortable with the honing steel is a must for better home-cooking.

Sieve all the things.

Mesh sieves, drum sieves, metal sieves - I’ve never seen, and certainly not used, such a number of variations of tools-with-tiny-holes-in-them as I have here.

Some uses of the sieves are obvious: straining sauces to remove the vegetables and meat chunks that it was cooked with, sifting flour before we use it.

But others ways we use a sieve are seemingly excessive, but make a huge difference in the final texture of a dish.

We press boiled potatoes through a drum seive to make perfectly creamy puréed potatoes - infinitely more elegant than simply “mashing” them. We strain beaten eggs through a sieve, to remove bits of eggshell or clumps of white, leading to a much more even omellete or scramble. We let sautéed spinach sit on a sieve, to release its excess moisture and greatly improve the texture and mouthfeel.

Sieves are the perfect tool for ensuring a light, even texture. I’m absolutely going to stock up.

Make sauces.

So much of French cuisine is characterized by the rich variety of sauces.

Indeed, in many of our dishes, the sauce was the flavor. The majority of the ingredients we’d use - carrots and leeks and celery and herbs and spices - would go into the sauce, most of it to be strained out before the sauce was finally served.

Though “classic” French sauces can be wildly complex, the basic pan sauce is simple and effective, and I can’t imagine serving a meat without it. The pan sauce formula:

- Brown a your meat in a pan. Don’t use non-stick! You want all those little bits of carmelized meat - the “sucs” in French, or the English “fond” - to stick the the pan, as it will form the hearty flavor of your sauce.

- Remove the meat, and cook some finely-chopped aromatic vegetables in the same pan, with a bit of fat. Usually this will be onions or shallots. Sweat until fragrant and translucent.

- Deglaze the pan - add in a layer of liquid, white or red wine or stock, to the hot pan, causing a nice satisfying sizzle and releasing the sucs at the bottom of the pan. Scrape these sucs with a spatula to free them.

- Reduce the liquid until it is syrupy.

There are infinite variations on this theme - adding a large amount of stock and reducing, adding different aromatics, adding flour to thicken the sauce, adding cream, mounting with butter. But the combination of seared meat + pan sauce will be a staple of my kitchen improvising.

Presentation matters.

I rarely take the time to carefully plate a dish a make at home.

But taking time to elegantly plate a dish makes such a difference to the people you’re cooking for. Above all else, a well-plated dish communicates the care you put into preparing it. Spending two hours over a stove only to slop the result onto a plate does a disservice to all your hard work.

And beautiful plating doesn’t have to be hard! A few tips:

- Above all else, make sure the plate is warm. Warm plates keep the food warm, letting you savor your meal longer.

- Aim for an even mix of colors and shapes around the plate - a “bountiful garden” on the plate. If your recipe combines a mix of different colored meats or vegetables, arrange them so the colors are evenly dispersed. This is more pleasing to look at, easier to eat, and implies a more even flavor.

- Buy some cheap ring molds. A nice circle of food is so much more elegant than a scoop. And takes almost no effort - place a ring mold in the center of a dish, and scoop in your food - whether it’s a stew, or rice, or pasta. Remove the mold, and voila - a perfect circle of deliciousness.

- Use garnishes that evoke the flavors of the dish. Save pretty little leaves from your ingredients - whether carrot tops, or parsely sprigs, or celery leaves - and add them to finish your plate. The best garnishes give the sense of what the dish will taste like - they serve to visually highlight the flavors of the meal.

Jun 27 2018

“To understand cuisine, you have to understand the culture and way of life.” – Chef Guillaume, at Le Cordon Bleu

Founded in 1635 by Cardinal Richelieu, the “Académie Français” is France’s national institution dedicated to the codification and preservation of the French language. Made up of forty members who hold office for life - modestly called “Les Immortals” - the Academy is tasked “to work, with all possible care and diligence, to give certain rules to our language and to make it pure, eloquent, and capable of treating the arts and sciences.”

Richelieu, ever on the hunt for new and creative ways to consolidate power of the French monarchy, saw language as an instrument of policy - that centralizing the governance of the French language could serve to further unite Francophone society under the crown.

The practical function of L’Académie has been to publish the official French dictionary, the “Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française”. It has published eight complete editions over its nearly four hundred-year history, the most recent edition having been put out in 1935. Les Immortals are hard at work on the ninth edition, having just finished Maquereau through Quotité. Their greatest challenge is deciding when new words deserve to be added to the official language - recent additions include words like “parka,” “photocopy,” “piano-bar,” and perhaps as a sign of the times, “dope,” “joint,” and “marihuana.”

If there was a “Dictionnaire” for French cooking, it would be “Le Guide Culinaire” by legendary French chef Auguste Escoffier. “Le Guide Culinaire” is the bible of French cuisine - codifying everything from the base stocks, to the “mother sauces,” to all the classic French recipes, to the “brigade system” of chef hierarchy and how kitchens should operate. Its iconic 1921 edition was designed for use by professional chefs, but also explicitly to educate the younger generation of cooks in the French culinary tradition. The fat and butter content of the recipes doesn’t exactly align with the modern diet, but Le Guide is still actively referenced in kitchens and used as a textbook in cooking schools.

French language, cuisine, and history are deeply intertwined. It is said the Eskimo language has fifty different words for “snow;” the French language has separate, unique words to describe nearly every specific, esoteric cooking technique.

“Singer” is to sprinkle a sauce with flour at the start of cooking, to give it a particular consistency. “Fleurer” is the specific gesture of dusting a countertop with flour, before rolling out dough. “Fondre” is to cook certain vegetables in water and butter, covered, until the liquid has evaporated, without browning. “Fraiser” is a technique for mixing dough evenly by smearing it with the fleshy part of the palm of the hand.

Other words are charmingly used to describe aspects of the cooking process. A lightly sizzling pan is described as “singing.” Little fat bubbles on the top of a pot of liquid are called “eyes.” To trim egg-white filaments from a poached egg is to “ébarber” - to shave it, like a beard.

Preparation styles of dishes have different names, depending on what vegetable is used as the base. A dish “Du Barry” means it’s made with cauliflower. “St. Germain” means white beans. “Clamait” peas, “Crécy” carrots, and “à jeuntuil” asparagus.

And history is preserved in dish names. “Crème du Barry” - a lush, creamy, and pure white cauliflower soup - is said to have first been prepared by a chef in love with the mistress of King Louis XV, the Comtesse du Barry. Taken by the Comtesse’s fair skin - “white as the full moon” - the chef wanted to create a soup as elegant and light.

“Lamb Navarin,” a lamb stew with carrots and turnips, comes from the 1827 Battle of Navarino, where an alliance of French, Russian, and British troops handily defeated Egyptian and Ottoman forces during the Greek war of independence. The French troops supposedly mocked their opponents, calling them “navets” - turnips - and a dish was created to commemorate the victory and wordplay.

Vegetables cooked “à l’anglaise” - “in the style of the English” - are boiled in heavily salted water, and served without sauce. The French saw British cuisine as comically simple, just having everything salted and boiled to mush, and so named this cooking style for their rivals across the Channel.

And Napoleon supposedly hated his vegetables being served in different sizes and shapes. So the “tourné” technique - “turning” vegetables like potatoes by cutting them into football-shaped oblongs - was created, and has remained a staple of elegant French dish presentation.

French cuisine, like the French language, remains a unifying force for modern France; a preservation of its history, a point of pride for its culture, and recognized internationally for its elegance and structure. Cardinal Richlieu would be proud.

But there is a central question that dogs French cuisine, and its bastion at Le Cordon Bleu. The same central question that drives L’Académie Français and its Dictionnaire. Indeed, perhaps the most challenging question for modern French society.

How do you reconcile the preservation of history, culture, and tradition, in the face of modern social and demographic change?

An important aspect of the culture itself is creating and passing down artifacts of its own preservation. French cuisine is an amber, trapping moments in history - beautiful Comtesses, idiosyncratic emperors, military victories - in the form of food. Each bistro becomes a museum, a temple; each dish a diorama; honoring tradition and the very act of doing things the same way they have always been done.

But diets change. Tastes change. “Fusion” restaurants push out traditional French establishments. Is this cultural evolution, or cultural destruction?

There are no French nationals in my class of nearly thirty at Le Cordon Bleu Paris. We come as pilgrims from countries all over the world, to learn and worship at the mecca of traditional French cuisine. We’ll all return home and bring a piece of French culinary history with us. This is preservation through education, through sharing. As the world comes to France, France also expands to the world.

Cardinal Richelieu’s legacy is a topic of debate among historians. But it is well understood that he brought what was a loose collection of squabbling feudal lords together into a cohesive, singular, internally-peaceful state.

In Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1839 play “Richelieu; Or the Conspiracy,” the Cardinal Richelieu character utters the famous line: “The pen is mightier than the sword.” Perhaps the fork can be pretty mighty too.

Jun 20 2018

6:30am

Punctuality.

Hammered in from orientation day at Le Cordon Bleu: punctuality is paramount. Luckily the summer Parisien sun is well-risen at this point, making it a little easier to make my 7am metro. Classes start at 8am sharp, so 7:45 is on-time.

7:30am

The Cordon Bleu locker room is my cramped home-away-from-home. It takes 15 minutes to get into the full uniform, required for each class:

- Special kitchen shoes - black, slip-proof, reinforced.

- Black socks.

- Houndstooth navy-and-white chef pants.

- White undershirt.

- Chef’s jacket, the pièce de résistance.

- White hankerchief-style necktie.

- Pen, fork, and spoon in the left shoulder pocket of the chef’s jacket.

- Recipe notebook.

8:00am

“Bonjour tout le monde.”

“Bonjour Chef.”

The first class of the day is typically a “demo,” where we watch the chef prepare two dishes, the main one of which we’ll replicate in our following “practical.”

Demo classes are taught in French, with a live translator in the room to translate to English. The translator takes roll at 8am sharp, and the chef begins.

The demonstration is more performance than lecture. There are five or six different chefs for the Intensive Basic Cuisine, who rotate between demos and practicals. Every one of them is like a charismatic college professor, or a one-man show, their cooking space their stage. Glass mirrors on the ceiling give a top-down view of their worktop, and cameras and TV screens around the room make for a live-produced cooking show.

The chef glides between mincing vegetables and stirring hot pans, peppering in historical backgrounds of the dish or war-stories from their careers in the kitchen.

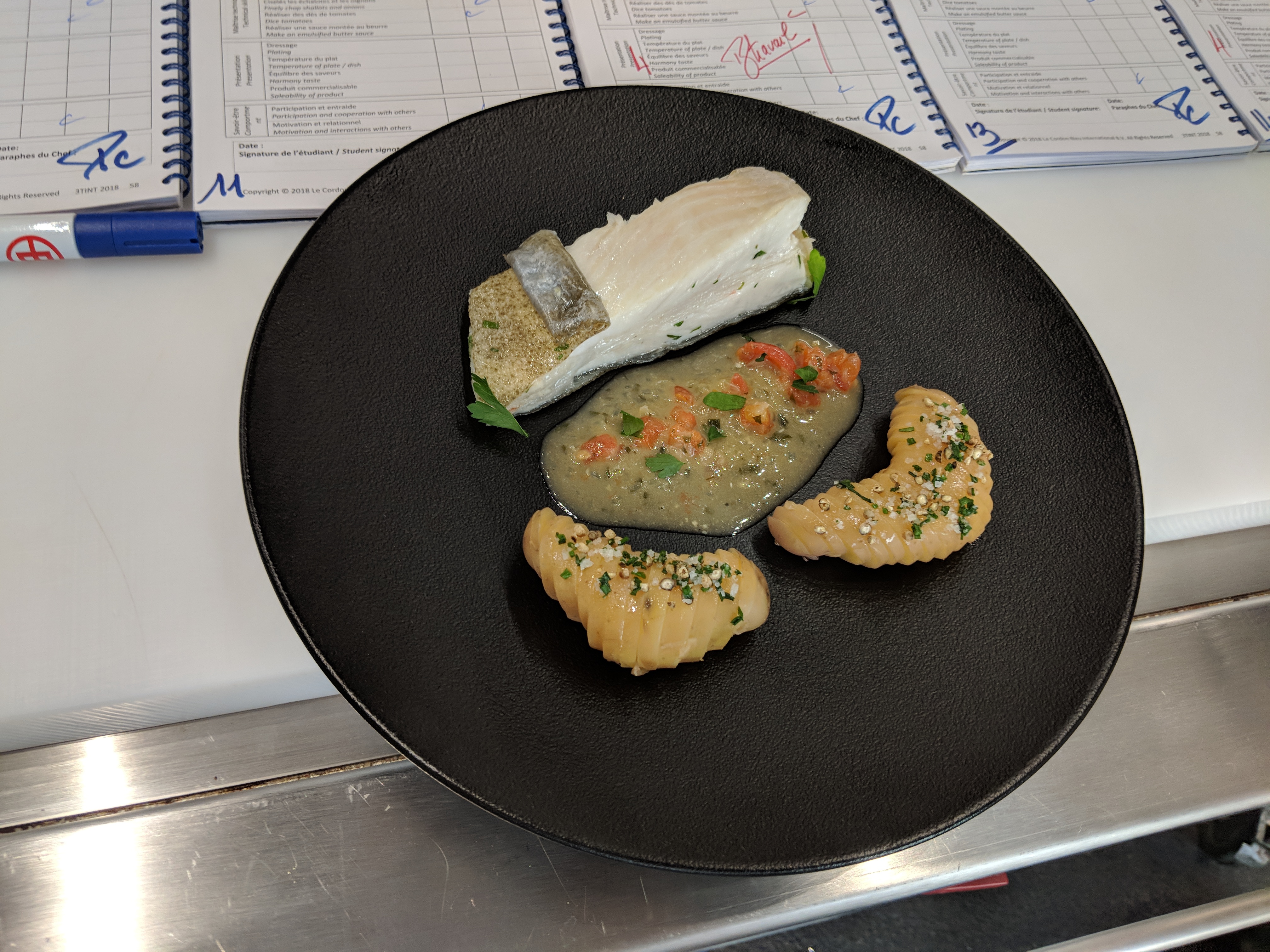

Today’s dish is a “Troute meuniere Grenobloise with almonds, Anglaise-style potatoes.”

For each recipe, we’re provided an ingredients list with measurements, and blank space for our notes. At the highest level, the steps for the recipes are simple - gut the fish, prepare the Grenobloise, turn the potatoes, start the sauce.

But a successful final dish is all in the details. Forget to remove the gills from your trout? The chef will notice when you present your plate. Accidentally carmelize the base for your white sauce? You’re white sauce is no longer white, and there’s no going back. The class asks questions throughout the demo so we don’t miss a detail.

Other than having some vegetables pre-peeled and cut, the chefs don’t skip steps. There’s no cooking show-style deux-ex-machina “and now we’ll just take this finished product out of the oven.” Hour-long baking times take an hour, a thirty-minute sauce takes thirty minutes - they’ll work on other parts of the recipe during the wait.

10:50am

“Degustation.” The best part of the day.

At the end of every 3-hour demo, we each get a tiny portion to taste what the chef has made. Unfailingly spectacular. A few flakes of fish, a couple toasted almonds, a slice of potato. A few drops of salty, gooey, spoon-coating sauce. The payoff.

11:00am

Our first break of the day. We hit the cafe in the ground floor of the school for a captive-audience-priced lunch and a coffee.

11:40am

Back to the locker room to change into cooking gear. For the practicals where we’re doing the cooking, we add a few accessories to our basic chef’s uniform:

- Apron.

- Tea towel.

- Cook’s hat.

- Knife bag, which holds our personal set of knives and other kitchen tools.

- Net bag with our scale, timer/thermometer, and tupperware.

- Evaluation notebook, where the chef gives us grades on each plate.

12:00pm

Practical.

We enter the long, narrow working room. Our abbey, our battlefield for the next three hours.

There are fourteen workstations - seven on each side. Combination stovetop/ovens run down the center of the room, with countertops along the walls.

Stations are numbered - I’m 13, halfway down the right. Each station has a set of pots, pans, bowls, and strainers, a drawer to store knives and tools not currently in use, and about a square meter of workspace. A sink and trash can is in each corner of the room, communal oils, seasonings, and pantry items run down the center.

We’re each given a tray with our ingredients - today, a few potatoes, sprigs of parsely, toasted almond slivers, two lemons, sandwich bread for croutons, and two whole trout.

The room is eerily quiet - we don’t waste a second. We take out our knives and other tools we’ll need for this particular dish - a 10” chef’s knife, paring knife, turning knife, peeler, channeling tool, scraper, tongs, spatula, and scissors.

Work is fast, bordering on frantic. We have 2 hours 30 minutes to cook, plate, and present our dishes in each practical, and every day we take up every second.

Cuts and burns are constant. A chef knife slips while you’re slicing almonds and you end up with a slice of thumb. You take a plate out of the oven, then forget it’s hot and grab the handle, cooking your palm. I’ve earned a few large arm burns from hot pans, lost part of a nail to the chef’s knife, stabbed a thumb with a meat fork, and shamefully gave myself a blister whisking a sabayon.

But I’ve fortunately been spared some of the more gruesome injuries. The mandoline is a particular death trap - waffle-cutting potatoes left a student with a perfectly zig-zagging gash down their palm. Another seared both hands grabbing a stockpot out of the oven. And the near-misses - we’ve splattered fry oil, dropped knives, set kitchen towels on fire.

The practical continues at a hectic pace. Students rush around the room, aprons stained with fish guts. Oil sizzles and crackles, knives knock against cutting boards. Someone gets a whiff of singe and shouts “something’s burning!” Someone else grabs and hot pan and immediately drops it on the table.

Slowly-but-surely though, the smell of fish sautéed in butter fills the room.

2:27pm

Plates are due to the chef precisely two and a half hours after the practical starts.

After over two hours of cooking, the last few minutes are the most important. All the pieces typically come together at once - the meat, sides, sauce, and plate must all be served hot, meaning stovetops and ovens are packed, sometimes with multiple pots sharing the same burner, each piece of the puzzle straining for a touch of heat.

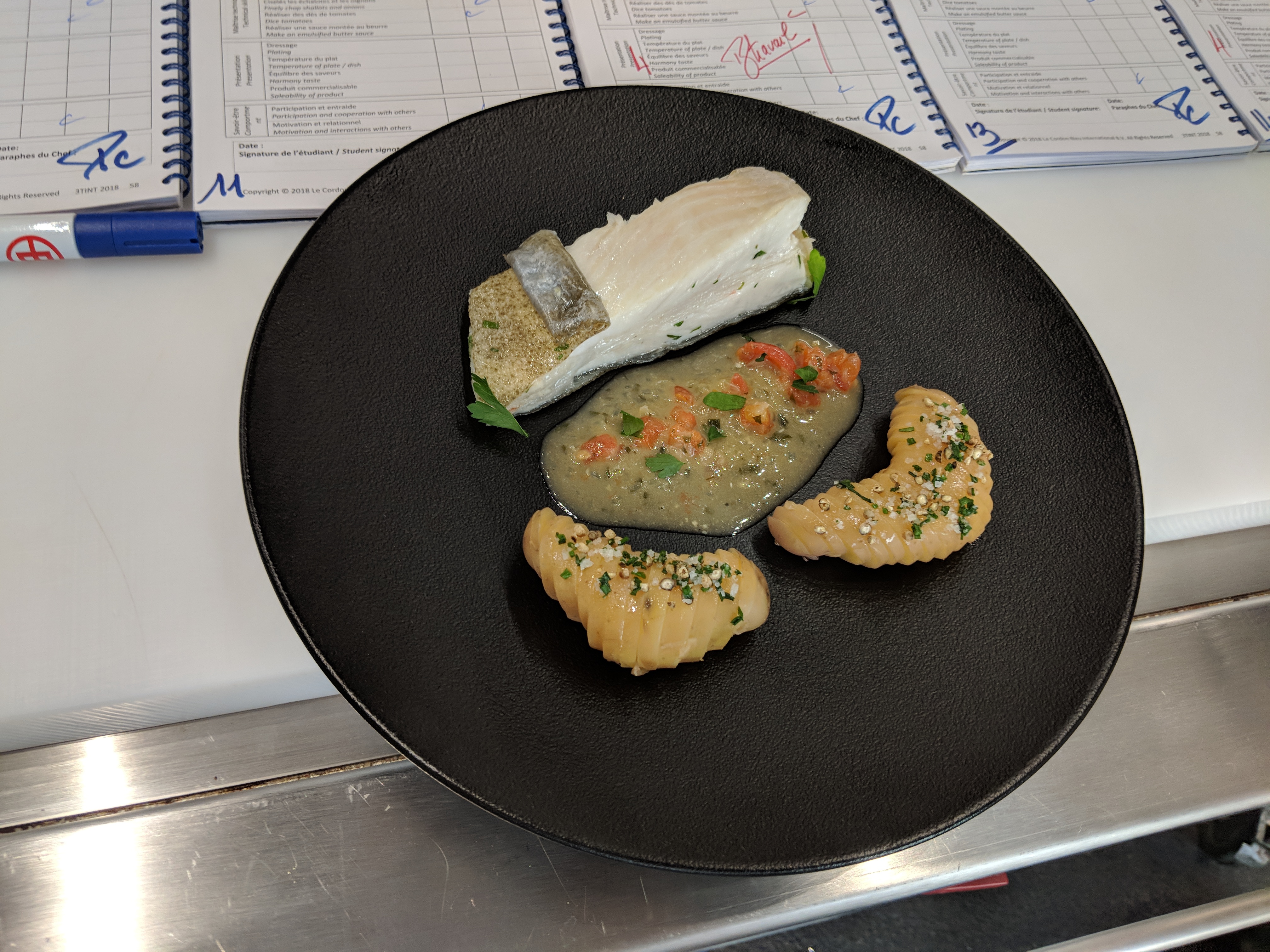

Dishes must be plated precisely like the photo, down to the last minor detail. Fish facing the wrong direction on the plate? The chef will notice. You’re not supposed to use your fingers - tweezers and spoons alone - but it’s nearly impossible in the frantic rush to get each slice of parsley to lay just right.

And then you present to the chef.

They take a small bite of the fish. They test each vegetable on the plate with a paring knife, to see if it’s cooked through. They taste your sauce.

“Pas mal.”

The chef then leaves you grades in your evaluation notebook. Sixteen different categories, under groups like “hygiene,” “organization,” “technical skills,” “presentation,” and for each you get one of three grades: 😁 😐 🙁. Along with a few notes: “Cook potatoes more!” “Brown your butter!”

2:31pm

Cleanup.

Cleaning the practical room is as frantic as cooking the dish. Each station must be complete, and with 28 different pieces it’s easy to lose track. As the dishwasher finishes, students try to gather a complete set of tools for their workstation.

3:00pm

A deep sigh of relief.

On good days, we’ll now be finished. More likely, we’ll have a lecture class - a more traditional-style three-hour lesson about product seasonality, or hygiene practices, or the different cuts of meat, or dairy theory. Or another demo. And sometimes another complete demo-practical pair. On four-class days we’re not out until 10:00pm.

And the next day we’re back. Six days a week, Monday through Saturday. Thirty recipes over just under five weeks.

It has been far more intense than I imagined. Demos are peak focus, for three hours straight. Practicals are peak stress, for three hours straight. Literal blood, sweat, and tears go into each dish.

Here, as everywhere, the “medium is the message.” Hard work, discipline, and a generous dash of suffering is the lesson. This is not about learning new recipes. This is not about honing skills to be a better home chef. This is training to work in a kitchen. It’s demanding, it’s physical. A chef at a Michelin restaurant won’t tolerate you being late, so you can’t be late here. Professional kitchens are hot, stressful, cramped places, with little room for error, and so it is here. You cut and burn yourself in the kitchen and have to keep moving on, and so it is here.

The first step in most recipes is to take your raw ingredients and break them down. Vegetables are washed and peeled and minced and sweat to form the base of a sauce. Bones are burned and carmelized. Fish are gutted and fileted. Only at their smallest, at their most worked and cut up, do these ingredients reveal their best flavor. It’s only then that you begin to build back to the dish itself. And so it is here.

Passion is not loving something at its best, at the end result. Everyone likes good music. Everyone likes good food. Passion is loving something at its worst. At its most base, most tedious, most soul-crushing.

The first few weeks have been a test of grit, and a test of passion. It’s rare you get to experience something so intensely distilled. Something to struggle with, something to savor. There’s a certain clarity to it.

Jun 15 2018

The word “propre” in French can have two different meanings, depending on its position in a sentence. It can mean “own,” as in “I have my own restaurant” - “J’ai mon propre restaurant.” Or it can mean “clean” or “tidy,” as in “my clean plate” - “Mon assiette propre.”

Working clean - working “propre” - is the first and constant lesson of Le Cordon Bleu.

In a “propre” kitchen, everything has its place.

The setup in the practice kitchen is extremely precise, organized identically each time.

We place our knives in the same place in the drawer, along with a whisk, rolling pin, scraper, and any other specific tools we might need for the particular recipe. A single shelf below our work surface holds our other tools:

- A cutting board.

- Five nested bowls of increasing size and topped by a measuring cup and placed in two trays.

- Four increasing-sized saucepans stacked in a stockpot placed on a large sautee pan.

- A sieve and metal strainer stacked together.

- Two non-stick frying pans and one rounded- and one flat-bottomed sautee pan stacked together.

A four induction-burner stovetop is behind us, with an oven below. We prepare every dish on our roughly 4x4 surface.

Our work must also be done in a “propre” manner.

The chefs tell us “in order to work well, you need to have the right method.” The method for working propre is to “arrange, work, clean, repeat.”

Only one thing is worked on at a time, with only the tools needed for that particular job on the work surface.

If you’re washing your vegetables, you prepare your counter with only a tray of dirty vegetables on the left, a bowl of water in the center, and a tray for clean vegetables lined with paper towel on the right. You wash one at a time, moving left to right: dirty vegetable goes in the water, is washed, and is placed on the clean tray. Trays are then wiped, water is emptied, work surface is wiped.

Then you peel your vegetables - a tray of washed vegetables, a bowl for peelings, your paring knife, your peeler, and a tray for the peeled vegetables. Peel. Bowl is emptied and removed, knife and peeler in the drawer, work surface is wiped.

Then you cut your vegetables - a tray of peeled vegetables, a cutting board, a chef’s knife, a scraper, a bowl for trimmings, a tray for cut vegetables. Cut. Bowl is emptied, work surface is wiped.

Arrange, work, clean, repeat.

Every cooking session continues this way. Never an unnecessary tool or bowl. Never a stray scrap on the counter. Chef is strict, and is unbending when it comes to working propre. An idle fork or paper towel will be spotted from across the room: “Qu’est-ce que c’est?” “What is that?”

“Cuisine is militarized,” Chef reminds us. An elite kitchen is a fast-paced, dangerous place, requiring absolute precision. Working “propre” is about developing reflexes and intuition, so the basics become automatic and the complex becomes the sole focus. If you know where everything is at all times, if the only objects in front of you are the ones you’re actively using, you don’t have to think. You just do.

Working this way is compulsive. It’s infuriating. But after getting used to this structure, I’m realizing how crucial it is.

Working propre is working safe. Without stray knives laying around, you can’t accidentally grab something sharp. Without stray bowls and ingredients lying around, and wiping down your surface after every step, you lessen the risk of cross-contamination. In the frantic chaos of the kitchen, method and instinct are the only way to reduce these risks.

Working propre is working clean. The surface remains clean, pots and pans remain either clean or with the dishwasher. There’s no massive final cleanup - cleaning is part of the cooking process itself.

And ultimately, working propre is liberating. You don’t get lost in your own chaos. There’s no “fog of cooking” obscuring the task at hand. When you work propre, you own your space, instead of letting your space own you. Things stop happening by chance. You become the master of your little universe, you see all the parts and pieces at all times. Your “espace propre” becomes “propre espace.”

Jun 11 2018

Orientation day at Le Cordon Bleu Paris.

About sixty students of all ages, from all over the world, sat down in the lines of chairs in the school’s banquet room. The proceedings started precisely on time, 8:30am.

Le Cordon Bleu representatives welcomed the new class, and launched into an introduction to the school. “Rigor,” “excellence,” “reputation” - no mention of “fun.”

They introduced the Chef instructors - the deeply experienced chefs, straight out of Central Casting for “French Chef,” who would be our professors for the program. And then we were shepherded into processing - to pick up our uniforms and equipment, and prepare for the first class.

The name “Cordon Bleu” has been associated with excellent French cuisine for centuries. In the 1500’s, King Henry III created “L’Ordre du Saint-Esprit” as the highest order of chivalry in the French Kingdom. This exclusive crew of knights and nobles knew how to throw a good party and became renowned for their over-the-top banquets, bringing in their greatest chefs looking to impress. The group’s symbol was a Cross of the Holy Spirit, worn by members at these banquets on a blue ribbon - a “cordon bleu.” The knights became known as “Les Cordon Bleus,” and the term “cordon bleu” came to be associated with excellence in French cooking.

Le Cordon Bleu as a culinary institution has been around since 1895, when French journalist Marthe Distel began writing a weekly culinary magazine, “La Cuisinière Cordon Bleu.” A small cooking school was started later that year, and has grown to be the pre-eminent school for training aspiring chefs in the French culinary tradition.

Today, Le Cordon Bleu offers nine-month diplomas in cuisine - cooking, patisserie - baking and desserts, and boulangerie - bread baking. Cuisine and Patisserie are broken into three levels - “basic,” “intermediate” and “advanced,” each three months of material. They also offer “intensive” versions of these courses - the same material but at double the pace, over six weeks. Students earn the “Grand Diplôme” when they complete all three levels of Cuisine and Patisserie - typically students looking to work in Michelin restaurants or start their own as head chefs. I am starting the “Intensive Basic Cuisine” course - so a six week crash-course through their first level of culinary art.

This orientation included students from all different courses and levels - there are about 28 in “Intensive Basic Cuisine.” Over 25 countries were represented - Korea, Tahiti, China, Israel, Canada, Brazil, Thailand, Russia, Iran, India, England, Mexico, Australia, and more, and a small handful from the US. Students are spread about evenly across the entire age range, from straight out of high school - there are even a few 15-year-olds in the class - to students in their fifties and sixties. Some have no professional cooking experience. Others have won “Master Chef” in their home country.

Classes are three hours each, and broken up between “Demonstrations” (Demos) and “Practicals.”

In Demo, students watch a Chef Instructor prepare a handful of different dishes, taking notes on the specific steps, techniques, cooking times, and helpful tips to work with the ingredients correctly and improve the dish.

Then in the following Practical, students cook the dishes themselves at individual work stations, ultimately presenting their plate to the chef at the end of the class for evaluation.

The classes are taught all in French, with a translator in the room during the Demo classes to translate after the chef to English. At orientation, we are given a binder full of each of the “recipes” - just ingredient lists and measurements, with blank space below for our notes - and a glossary of hundreds of French cooking terms.

The executive chef closed the proceedings: “I don’t do much except eat what you prepare, so it better be good.”

Jun 9 2018

“As I ate the oysters with their strong taste of the sea and their faint metallic taste that the cold white wine washed away, leaving only the sea taste and the succulent texture, and as I drank their cold liquid from each shell and washed it down with the crisp taste of the wine, I lost the empty feeling and began to be happy and to make plans.” – Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

French winemakers have a concept called terroir - a “sense of place” that is reflected in a wine.

Each plot of land that might grow a grape is unique. The way light strikes the field in summer, the way the temperature drops as the sun sinks below a ridge, the way the rain runs down this particular hillside and into the soil, the way the fog blankets a valley floor - a millenia of geological and environmental processes come together to produce each vine. And the wine from these grapes, in turn, becomes the ultimate expression of this specific spot on earth.

Food can express its terroir too. Oysters take me straight to the sea. A dockside - clanging buoy bells, seagulls, a salty breeze, wood beams and rusted iron and tar - packed into a shell.

Certain oysters reveal an even greater precision. Since the Roman era, the Marennes-Oléron basin in the southwest of France has been the largest oyster-producing region in the world. Oysters there are grown and harvested in claires - shallow oysterbeds set into the coastline and protected from the ravages of the open sea.

The claires are oyster vineyards, with their own terrior. And oysters, as filter-feeders, are quite literally a distillation of their environment. Varying minerality, salinity, water temperature, tidal patterns, and local algae impart unique, distinguishing flavor to the oyster. Claire oysters are designated by their ripening time and the density of their oysterbed - the Pousse en Claire, grown with the lowest density of oyster per square meter, are the sweetest and fleshiest. A claire oyster doesn’t just transport you to the sea - it brings you to a point in the southwest of France, a particular estuary, tended a specific way, where oysters have been harvested for thousands of years.

So oysters made the perfect meal to settle into this new place. Alongside two friends, we collected ourselves each behind a dozen Fines des Claires and Speciale des Claires and dove into the sea, at the famed Huîtrerie Régis. A dozen claire oysters and a Sancerre is about as “Bienvenue à France” as it gets.

We’re all, to a degree, products of our own terrior - we project a sense of place from which we were raised. And the beauty of terrior as a concept is that it is not a value judgment. It is typically a compliment to say a wine, or an oyster, reflects a strong terrior. This simply means it intimately expresses its origin - that it is a genuine product of its surroundings rather than crafted to appeal to a certain audience.

Thirty-six Marennes-Oléron oysters certainly did the trick today. Despite June not being spelled with an R.

Jun 8 2018

Nothing lies so innocently, and so completely, like a recipe.

Their first words are lies.

“Prep time: 20 minutes” - except you’ll be slaving over a cutting board for an hour. “Serves 4” - prepare to be hungry, or to run out of tupperware.

Their instructions double down. Almost mocking.

“Dice the tomato,” read: “smash your mealy tomato into pulpy bits.” “Sautée until slightly softened” means “make hot until still too crunchy or hopelessly limp, or even better, a little bit of both.”

But the worst recipe deceit is the photo.

A glistening, perfectly cross-hatched steak, dusted with maldon salt crystals like snowflakes, pristinely plated on stoneware on top of linen on top of rustic upcycled acacia.

Your meal will not look like this. Your Ikea place setting is not the canvas for this masterpiece. And carefully plating your food just before you eat it is like making your bed just before you sleep in it: you wouldn’t regret it, but who’s got time for that.

I love to cook, but my cooking has admittedly always been firmly rooted in recipe. Robotically parsing instructions from some food blogger like they’ve been handed down from on high. Cooking should be an act of creation, but following a recipe becomes an exercise in replication - where the best you can do is not screw up. You own your work to the extent a scribe, or a forger, owns their facsimile, but there is always a hollownesss to cooking from an anonymous recipe.

There is safety though in following the recipe. Recipes let you strive for the platonic ideal they depict, while providing a safety net for when it inevitably doesn’t all quite work out. The timing is never right for an experiment - you don’t want your “personal touch” ruining a dinner party. And the last thing you want, after sweating over a hot stove for an hour, is to throw in an additional element of risk.

Diverging from the recipe means fully shouldering the burden of your creative success or failure. Going off recipe takes technique, taste, experience, and a bullish sort of confidence - to think “I can do better than this.” And it requires truly understanding and appreciating why the recipe is the way it is in the first place.

I believe that cooking well - that being able to create rather than replicate - is one of a privileged set of skills that directly leads to a richer, fuller life, for you and everyone around you.

That cooking well and living well are one and the same. That we follow recipes in our cooking, in our careers, in our lives, bland simulacrums of some long-forgotten seed of truth, lacking the confidence or wisdom to venture off the well-trod path.

I also like collecting diplomas.

So I’m spending the next six weeks at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, in their Intensive Basic Cuisine program. I have absolutely no idea what to expect. But I’ll catalog some of the things I pick up here.

And hopefully when I leave, I’ll be a little more comfortable going off recipe. But nothing really ends up looking like the picture.