Ways Culinary School Will Change the Way I Cook

Jul 3 2018So much of what I have picked up at Le Cordon Bleu is wildly impractical for home cooking.

Rarely will I have to behead a chicken, or gut a rabbit, in the comfort of my own home. I doubt I will ever brunoise a half-kilogram of carrots. I certainly hope to never turn a potato again.

But there are plenty of lessons that will absolutely help as I return to the life of a civilian cook.

Focus on ingredients & techniques, not recipes.

The “trick” to spectacular-tasting food is rarely in finding a magic recipe - it’s all in the ingredients, and the techniques you use in working with them.

A great home-cooked meal begins at the market. Fresh, high-quality ingredients stand on their own - they make your job easy as a chef.

Then it’s all about technique. Recipes rarely focus on technique - they list the steps you need to cook the dish, but there’s so much space for perfection in how each step is performed.

Nearly every dish we cooked at Le Cordon Bleu was remarkably simple - only a handful of common ingredients, and usually the only spices being salt and pepper. Yet from the exact same process and ingredients, the dishes the chefs make here are markedly better than what we create in our practicals. They are masters of technique.

A few examples of where technique makes all the difference:

- Sweating vegetables. The bases of most French recipes begin with “sweating” vegetables - heating them in oil or butter to soften and release flavor. Correctly-sweat vegetables make such a different in the final depth of flavor of a dish, and there are so many subtle aspects to getting it right: the right balance of fat to vegetable, the right size pan, the right order of adding ingredients, the right heat and time to let the ingredients release their flavor without browning or burning.

- Mixing ingredients. We’ll mix a liquid into a roux to thicken it, or mix liquids into flour to make a batter. You’d think “mixed” means “mixed” - just combine the two. But the key to a perfectly uniform, smooth mixture is to mix a little at first - to incorporate the two mixtures - then more and more at a time. This lets the ingredients blend slowly and evenly, minimizing lumps.

- Reducing sauces. We’ve become masters of reduction here - taking a large volume of a lightly-flavored liquid and boiling it down to create a small volume of a highly-concentrated sauce. They key is to reduce gently, using progressively-smaller pots as the volume of liquid decreases. Ingredients can scorch on the sides of a pot, leaving behind a slightly bitter burnt flavor. Too much surface area can cause a sauce to reduce too quickly, damaging the texture or flavor. A careful reduction is the key to a mindblowing sauce, and a mindblowing sauce separates the casual cook from the pro.

When it comes to ingredients, seasonality really matters.

Quality of ingredients will make or break a dish.

We don’t always have a fresh farmer’s market available to us though as we grocery shop. So how do you find quality ingredients at your local grocery store?

Stick to fruits and vegetables that are in-season. In US supermarkets - at least in California - we’re spoiled by having essentially the full range of common produce available year-round. This is a miracle of modern logistics and the global shipping industry, but a red-herring for good cooking. That winter tomato usually has been harvested while completely green and solid, and chemically ripened as it reaches its final destination.

Selecting produce that is in-season helps ensure that it has had time to develop and ripen naturally. This means richer, more developed flavors, easier-to-work-with flesh, and often also a lower price. Buying local and in-season isn’t a hippy-dippy luxury - it’s truly a win-win for any home cook.

Season, season, season.

Here to “season” a dish almost always means adding salt.

We’re constantly tasting and seasoning - meat before, during, and after it cooks; vegetables before, during, and after they are sautéed; sauces before, during, and after they are made.

A dish should never taste “salty.” But a perfectly-cooked dish, without any added salt, can end up entirely bland.

We keep ramekins of large-grained salt - similar to Kosher salt - on our workstations at all times, generously pinching it in throughout the cooking process. The salt is a natural disinfectant, and so can generally be left out in the ramekin indefinitely. It’s a must-have in any kitchen.

Breaking down meat, rather than buying fillets.

Before coming here, I didn’t know the first thing about gutting and filleting a fish.

In US supermarkets, meat is sold shrink-wrapped. It’s possible but rare to find many different varieties of whole fish. Certainly not rabbits. I can’t even imagine Safeway selling a chicken with its head still attached - even your “whole” Thanksgiving turkey will have its giblets conveniently in a little plastic bag.

At Le Cordon Bleu, breaking down meat and fish has been a large part of the instruction and technique. For fish and poultry, we’d always start with a whole animal. For meat, we’d often start with an untrimmed, un-deboned slab - even bacon for lardons would start out as a whole pork belly.

Breaking down your own meat is certainly not a no-brainer. It takes comfort and practice. It takes time. But the benefits are clear.

It’s cheaper - you’re not paying a premium for a butcher to do this for you. And you can use the whole animal for the rest of the dish. Fish carcasses would always form the basis for a fish stock, which would be used to cook the fish, and then would turn into a sauce. Meat trimmings would be browned to create sucs, to form the basis for a pan sauce. Chicken carcasses would become stock.

Breaking down meat gives you options. It gives you raw material and inspiration for additional dimensions to your dish. And it brings you closer to your ingredients. I probably won’t break down meat myself every time I cook, but it will absolutely become a part of my cooking repertoire.

Clean as you go. But actually.

“Clean as you go” is the mantra in the practical kitchens here. And I have no doubt I’ll bring this back with me - cleaning after every step when I cook.

Making a mess in the kitchen is a “boil-the-frog” problem. The mess starts slowly - a couple scraps on the counter, a dirty pan left in the sink - and slowly builds over the course of the recipe. Scraps become piles, a single pot becomes a tower, some splatters of sauce on the stove become a burnt-on crust.

Here, with a square meter of workspace, you can’t afford a mess to build up. The lack of clutter on a worktop removes that little nugget of stress in the back of your head - that nagging dread of “I’ll have to clean up all of this at the end.” Cleaning constantly actually makes the cooking process more enjoyable.

There are a few tricks I’ve learned to make it easier to “clean as you go”:

- Use a small bowl as a “counter-top trash-can.” Peel your vegetables over it, dump trimmings into it. And throw it out as it starts to fill up (or better yet, toss your scraps and peels into the compost!). This saves you trips to the garbage can, and gives you no excuse for leaving vegetable peels and onion skin on your cutting board.

- Heavy-duty “J Cloth”-style paper towels. Much thicker than your typical paper-towel, but more disposable than a kitchen rag, these are a godsend in the kitchen. Use them to wipe down counters, clean them in boiling water or even the dishwasher, and throw them out guilt-free. The chefs keep one slightly damp on their workstation at all times, to wipe down any splatter as soon as it happens.

- Wash pots and pans as soon as they’re finished. We cheat here in our practicals a bit - there’s a professional dishwasher who cleans our pots and pans as we cook. But the principle we follow carries through to home cooking - as soon as we’re done with a pot or a pan it goes straight to the dishwasher, rather than hanging out on our stove or countertop. This way they’re available to use again if needed, they don’t clutter our workspace, and there’s not a single massive effort at the end to clean every pan. At home, I’ll put pots and pans in the sink as soon as they’re done, and use any free moment during the recipe to clean whatever is in the sink as quickly as possible.

- Store multi-use tools like spoons, whisks, spatulas, and tongs in water. It’s tempting to take out your wooden spoon, give a pot a stir, and then leave the spoon on the counter. But you end up with drippings on the counter, and crusts of whatever you stirred last stuck to the spoon. I leave a small pot or measuring cup with water near the stove, with all my stirring and tasting tools dipped in it - to keep them clean in-between uses, and avoid a grungy build-up on my worktop.

- Use cupcake wrappers or small foil tins to hold cut & measured ingredients before you’re ready to use them. If you’re cutting vegetables, or measuring out spices, or prepping herbs, store them in small disposable cups to stay organized without dirtying more bowls. This way you can prepare your complete “mise-en-place” before you actually begin cooking, making the actual cooking process a breeze.

- In dire situations, plastic wrap your cutting board. If you’re breaking down something especially messy - raw meat, or scaling a fish - cover your cutting board with plastic wrap first. This lets you just bundle up the mess and throw it all out, before moving on to your next step.

Embrace the power of the scraper.

The humble plastic bowl scraper. Initially designed to get every last drop of batter out of a bowl, the scraper is easily my second-most-valuable tool (after the chef’s knife, of course).

I use it to keep ingredients in a neat pile on the cutting board - rather than scraping with the knife blade, which both damages the knife and also likely my hand. I use it to collect ingredients off a cutting board and transfer them - much neater than trying to scoop with my fingers. I use it to clean the countertop - brushing every last crumb or piece of vegetable off the edge and into my trash bowl.

It takes a little work to get into the habit of reaching for the bowl scraper, but once you get used to it you’ll never go back. Any time you take out a knife, take out a scraper.

Use the right knife for the job.

I’ve always thought that a “real” chef only needs one knife - their 8-10” chef’s knife.

I could not have been more wrong.

A key to professional-level cooking is precise cuts, and precise cuts require precise equipment.

The chef’s knife is still the anchor in my toolkit, but I’ve come to appreciate the value of each of the different primary kitchen knives.

I use my paring knife like an extension of my fingers. It’s perfect for precisely cutting small vegetables like garlic or shallots. But more often, I won’t be holding it by the handle - I’ll hold directly on the blade, and use it for peeling things like a tomato by grabbing the skin between the blade and my thumb.

I can’t imagine filleting a fish without a filleting knife - the thin and flexible blade countours precisely to the bones of the fish, making it easy to slice way flesh with minimal wastage.

And the cleaver makes it easy to process cuts of meat - even full carcasses like chicken - that I never would have attempted to tackle before.

Hone knives.

The honing steel. It comes with every complete knife set - a long, thin, cylindrical piece of metal, with a guarded handle. We can all envision chefs using this tool - deftly sliding a knife blade across it with that distinctive metallic shing.

I’ve known the purpose behind the steel - re-aligning the microscopic teeth along the very edge of a knife’s blade, to help it cut more precisely. I’ve been taught how to use it in the past - make a 15-20° angle between the blade a knife and steel, and swipe it from heel to tip, 3-4 times per side. But I’ve never really felt compelled to hone my knives in my home kitchen.

Now I can’t imagine starting to cook before honing my knives.

When you cook a couple times a week, maybe cutting a vegetable or two and never really focusing on the precision of the cut, it’s hard to really notice as a sharp knife slowly becomes less-than-sharp. Usually the dire condition of your blade will only become obvious once it starts crushing tomatoes instead of slicing through them.

But cooking multiple times a day, processing baskets of vegetables each time, an even slightly un-honed blade became painfully obvious - often literally so. A dull blade will slip on precise cuts - the easiest way to nick yourself. And it will slow your whole cooking process down, requiring more pressure and slower movements to make the same cuts.

Sharp, precise knives absolutely make a difference in the final result. More thinly, precisely-cut vegetables release flavor more readily and evenly, and lose less moisture onto your cutting board. Vegetables cut with a sharp blade will tend to oxidize less, leading to better coloring and less risk of off-flavors in your final result. And working with a sharp knife will be safer and faster.

Getting comfortable with the honing steel is a must for better home-cooking.

Sieve all the things.

Mesh sieves, drum sieves, metal sieves - I’ve never seen, and certainly not used, such a number of variations of tools-with-tiny-holes-in-them as I have here.

Some uses of the sieves are obvious: straining sauces to remove the vegetables and meat chunks that it was cooked with, sifting flour before we use it.

But others ways we use a sieve are seemingly excessive, but make a huge difference in the final texture of a dish.

We press boiled potatoes through a drum seive to make perfectly creamy puréed potatoes - infinitely more elegant than simply “mashing” them. We strain beaten eggs through a sieve, to remove bits of eggshell or clumps of white, leading to a much more even omellete or scramble. We let sautéed spinach sit on a sieve, to release its excess moisture and greatly improve the texture and mouthfeel.

Sieves are the perfect tool for ensuring a light, even texture. I’m absolutely going to stock up.

Make sauces.

So much of French cuisine is characterized by the rich variety of sauces.

Indeed, in many of our dishes, the sauce was the flavor. The majority of the ingredients we’d use - carrots and leeks and celery and herbs and spices - would go into the sauce, most of it to be strained out before the sauce was finally served.

Though “classic” French sauces can be wildly complex, the basic pan sauce is simple and effective, and I can’t imagine serving a meat without it. The pan sauce formula:

- Brown a your meat in a pan. Don’t use non-stick! You want all those little bits of carmelized meat - the “sucs” in French, or the English “fond” - to stick the the pan, as it will form the hearty flavor of your sauce.

- Remove the meat, and cook some finely-chopped aromatic vegetables in the same pan, with a bit of fat. Usually this will be onions or shallots. Sweat until fragrant and translucent.

- Deglaze the pan - add in a layer of liquid, white or red wine or stock, to the hot pan, causing a nice satisfying sizzle and releasing the sucs at the bottom of the pan. Scrape these sucs with a spatula to free them.

- Reduce the liquid until it is syrupy.

There are infinite variations on this theme - adding a large amount of stock and reducing, adding different aromatics, adding flour to thicken the sauce, adding cream, mounting with butter. But the combination of seared meat + pan sauce will be a staple of my kitchen improvising.

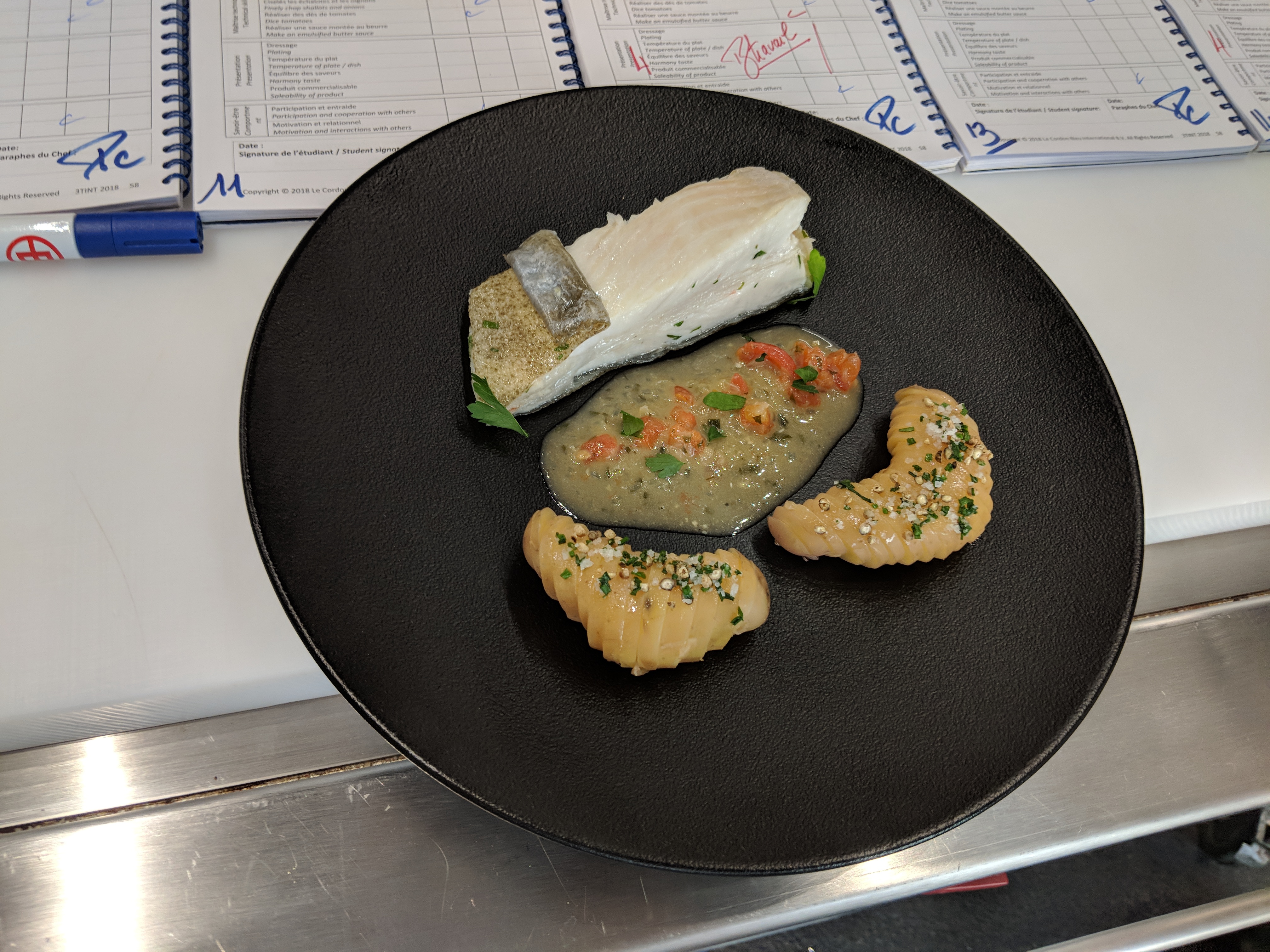

Presentation matters.

I rarely take the time to carefully plate a dish a make at home.

But taking time to elegantly plate a dish makes such a difference to the people you’re cooking for. Above all else, a well-plated dish communicates the care you put into preparing it. Spending two hours over a stove only to slop the result onto a plate does a disservice to all your hard work.

And beautiful plating doesn’t have to be hard! A few tips:

- Above all else, make sure the plate is warm. Warm plates keep the food warm, letting you savor your meal longer.

- Aim for an even mix of colors and shapes around the plate - a “bountiful garden” on the plate. If your recipe combines a mix of different colored meats or vegetables, arrange them so the colors are evenly dispersed. This is more pleasing to look at, easier to eat, and implies a more even flavor.

- Buy some cheap ring molds. A nice circle of food is so much more elegant than a scoop. And takes almost no effort - place a ring mold in the center of a dish, and scoop in your food - whether it’s a stew, or rice, or pasta. Remove the mold, and voila - a perfect circle of deliciousness.

- Use garnishes that evoke the flavors of the dish. Save pretty little leaves from your ingredients - whether carrot tops, or parsely sprigs, or celery leaves - and add them to finish your plate. The best garnishes give the sense of what the dish will taste like - they serve to visually highlight the flavors of the meal.